I would roughly say that, in English-translated works, there have been two general historical accounts of the phenomenon called “otaku” : the first, embraced by Toshio Okada, reads in otaku practices the expression of something specifically Japanese. For example, Okada roots otaku’s obsession with encyclopedic knowledge in 18th century Edo period art criticism and trade. On the other hand, other scholars have focused on otaku as something indeed distinctly Japanese, but that emerged contingently, after the defeat of Japan in World War II and as a reaction to either atomic warfare (Takashi Murakami) or American culture (Hiroki Azuma).

The first thesis can easily be (and has been) critiqued for its methodological nationalism, which supposes a Japanese historical essence that would legitimize otaku as a part of a greater national movement. This is in fact a general deadlock faced by most Japanese scholars on otaku : whether it is because they embody an alternative to Western modes of representation (Murakami) or of a general shift towards the postmodern (Azuma), otaku are always the vanguard, the proof that the Japanese are ushering towards a new age, before other nations and peoples [Lamarre, 2009 ; Galbraith et al. 2015]. However, I believe that such a general historical vantage point has an advantage that may allow us to reconsider the question of nationalism and historicism : it conceives otaku as something positive (and not just a reaction to a historical event) and as a transhistorical object that allows us to think of the otaku as a general attitude towards art and/or media. For example, Okada’s characterization of the three key “eyes” of the otaku (the “eye of sophistication”, the “eye of the craftsman” and the “eye of the expert” ; see Okada, 2015, p.97) can be reinvested to describe general attitudes of consumption or criticism.

But then this must not become an idolization of otaku, which would make them a paradigm for any relationship with media. Moreover, it does not dispense us of historical discourse : without it, we have no way of understanding what’s so specific about otaku and their evolution. We risk making of otaku simply a general attitude and just frame it into the position of viewer or consumer. On the other hand, the historical approach allows us to make of otaku both an object (of historical study and of works) and a subject (the one that acts and creates the objects we study). What I would like to study here is precisely the way in which this double position has been established and evolved, both in regards to the specific characteristics of otaku culture, and to the more general stance adopted towards a general issue of Japanese contemporary history, that is, war and militarism.

Many have already argued that the connexion between otaku and militarism (sometimes even fascism) is a very close one [Murakami, 2005 ; Lamarre, 2009 ; Otsuka, 2008 ; Miyazaki, 2009]. But the issue is more complex : otakus’ fascination with war and weapons was always confronted to a strong anti-war discourse from otaku media themselves, most notably mecha series. This is why I will focus on three key works of the real robot genre : Mobile Suit Gundam, Super Dimensional Fortress Macross, and Macross : Do You Remember Love ? I will aim to show that, among others, these works were determining moments in otaku self-consciousness and that their different portrayals of war and technology may betray an evolution in this self-consciousness.

The emergence of otaku self-consciousness

Before coming to the works themselves, there are two questions that must be answered : 1) what do I mean, here, by otaku ? and 2) are otaku really portrayed in Gundam and Macross ?

To answer the first question, we must acknowledge the fact that the word “otaku” has always covered large and diverse categories of people and fans, from trains, to video games, to manga and anime… These different fandoms often intersect, but are not one and the same : just like some scholars suggest we should use anime in the plural and speak of animations [Lamarre, 2009], it might be more correct to think of otaku as a diversity. This is even more difficult considering that discourse about origins and birth of otaku in the course of the 1980’s is largely dominated by the Gainax myth and genealogy, whether it is in Yasuhiro Takeda’s Notenki Memoirs, which recount the history of the studio from its origins to Evangelion, Toshio Okada’s theory of otaku in Introduction to Otakuology, or fictional retellings of both these works in the anime Otaku no Video and the manga/drama Blue Blazes. This narrative tends to emphasize two aspects : the role of science fiction of any kind (from tokusatsu to robot anime) and of a mostly male fandom. Indeed, the issue of gender is not to be ignored here, and I will briefly touch upon it in this essay. Gainax was entirely created by men, and the account of the Notenki Memoirs rarely, if never, mentions women. This trend is the one I will mostly be analyzing, considering that it insists on the role of science-fiction and mecha anime in the formation of the otaku community ; however, science-fiction was far from the only place where otakus appeared. On the contrary, the very term “otaku” was first introduced in 1983 in a magazine, Manga Burikko, that focused around lolicon (1) and bishoujo rather than robots or SF. This emerged from shoujo manga, and the lolicon community was also one of the breeding grounds of what is now known as fujoushi, that is in a very few words, female otaku. For example, here is one of the first attempt at definition of the term given in June 1984 by the then magazine editor Eiji Otsuka : “First of all, because the term “otaku” will not make sense for new readers, I will explain. This is a made-up derogatory term to describe lolicon fans and anime fans, created by Mr. Nakamori Akio from Tokyo Otona Kurabu in a column previously published here in Burikko.” [Yamanaka, 2015, p.43]

As we can see, at the time, “otaku” was a neologism and did not immediately include SF fans like we retrospectively tend to think. Moreover, it was perceived as a “derogatory term” and was unlikely to be claimed by fans to describe themselves, except in a self-deprecatory meaning. Therefore, even though, for convenience’s sake, I will speak of “otaku” as a simple category, we can see that the issue is more complex, and that the SF fandom is far from being the only one to be considered. Most notably in the case of both the Macross TV series and movie, I will show that the integration of bishoujo characters to the real robot context was far from an innocent move. To quote Patrick Galbraith, “Macross is as much about falling in love with the cute girl character Lynn Minmay as it is about giant robots fighting in space”. [Galbraith, 2015, p.24]

Then there’s the second question. Considering that, as I’ve just shown, otaku didn’t exist as a self-defined or recognizable group when Gundam and Macross came out, it’s obvious that these works did not target or represent otaku in the conscious way later works did, from Otaku no Video to Evangelion. However, my argument would be that the characters and plots of Gundam and Macross helped shape otaku identity ; but to prove it, it is necessary to show that otaku did recognize themselves into the characters, before analyzing the common elements. I see three ways to demonstrate this point :

1. Chronology. One could argue endlessly on an exact chronology of otaku culture, especially its beginnings. However, the Gainax-inspired narrative compels us to insist on a few key dates : the Space Battleship Yamato series, in 1974-75, and especially its movie version, in 1977, which arguably triggered the SF boom in Japanese youth ; August 1981, with the holding of the 20th Japan Science Fiction Convention and the projection of the short Daicon III ; and, two years later, at the 22nd Convention, its sequel, Daicon IV. While other moments may be highlighted, the Daicon shorts are without a doubt a seminal moment, and an important one for historical perspective. Indeed, its overabundance of references to anime, SF, comics, pop culture, etc. constitutes a clear and conscious homage to the fandom and the objects of its admiration. In other words, along with the series of articles dedicated to “Otaku research”, which introduced the term (in June 1983, just before Daicon IV), it is without a doubt a reflexive moment for the community which, contrarily to Akio Nakamori’s articles, insisted on its unity, in spite of the diversity of its objects(2).

Within such a chronology, the works chosen fit perfectly : the Gundam TV series aired between 1979 and 1980 and the three compilation movies were released in 1981, the same year as Daicon III. Macross started airing in 1982 and finished in June of 1983, two months before Daicon IV ; and Do You Remember Love ? was released a year later.

2. Place in otaku tradition. Along with these purely objective coincidences, ideas and concepts introduced in this period and around these works became foundational for otaku identity. The first key event was the premiere of the Gundam compilation movies trilogy, on the 22nd of February 1981. During this “day when anime changed” [quoted in Clements, 2019], Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino declared “a new anime century” (anime shinseiki sengen). This was, just like SF conventions, a great moment for anime fans to meet and celebrate their love for media in a single place where they could celebrate their unicity and difference. The importance of this event was celebrated 15 years later in another masterpiece of otaku media, Neon Genesis Evangelion, whose Japanese title, Shinseiki Evangelion, directly references this day. But more importantly, Tomino’s declaration strongly associated otaku to a generational event, and in the context of the Gundam universe, to the Newtype character. Indeed, the “new anime century” is strongly reminiscent of the series’ “Universal Century” calendar in which a new type of human beings (shinjinrui) endorsed with psychic abilities, is emerging. The Japanese terminology, shinjinrui (literally “new mankind”, or “new human”), is far from innocent, as it was used in the 1970’s and 80’s to describe the baby-boomer generation – precisely that of the then budding otaku. It was then reinvested by otaku themselves : in the famous opening sentences of his Introduction to Otakuology, Toshio Okada describes otaku as a new step in human perception, in other words, as a new kind of human beings – shinjinrui. Evangelion’s main character’s name, Shinji, might also be a reference to the word, considering the phonetic similarity between the two.

As for Macross, its role may be made visible by its so-called contribution to the emergence of the word “otaku”. The first use of the term is, as I have shown, well documented ; its etymology is more debated, but there are some insights about its origin. The Japanese word otaku is a second-person pronoun, a particularly respectful one. Okada explains why it came to be used to describe anime fans :

“The accepted opinion for the time being in the otaku industry is that the rich kids who graduated from Keio University were the first to use the term “otaku”. They were ardent science fiction fans […]. Since they called one another “otaku” in front of fans at science fiction conventions, it is impossible that other otaku did not imitate them. For otaku, who have many opportunities to speak with people that they meet for the first time out of the necessity to exchange information, the term “otaku” is convenient, as it is a light form of address.” [Quoted in Aida, 2015, p.119]

Then, if we are to believe Okada, the term was already common before being used to designate a certain category of fans ; and one of the factors in the popularization of the pronoun was precisely the Macross series. Indeed, the male protagonist, Hikaru, refers to Lynn Minmay, one of the main female characters, as “otaku”. Tradition claims that, as a reference to their dialogue, Macross fans began to call each other “otaku”.

3. Otaku-like figures in the works themselves. I have already noted that the audiences of both Gundam and Macross, or at least the ones that left a valuable testimony, were mostly male. It is therefore first towards the male characters that the attention must focus ; and I believe that, especially in Gundam, they are both ideal figures of self-improvement that are to be imitated (3) and relatable characters that exhibit otaku-like behaviour. This is most visible in Amuro’s, Gundam’s protagonist, fascination with computers and technology : in the first episode, he is working on a computer and totally indifferent to the evacuation orders that are being issued, just like a stereotypical otaku might prefer to focus on his technological gadgets rather than pay attention to the real world. Moreover, Amuro’s otakuness is not just characterized by obsession : it is a real talent for all technology-related topics. Indeed, he is credited with having created, by himself, the robot Haro, and is able to pilot (although with little ease) the Gundam almost immediately after having read the instruction manual. Therefore, Amuro is not just otaku-like, but his talent for technological manipulation makes him an ideal figure for otakus – something which is also present in the theme of the Newtype, which I will explore later on.

In Macross, this theme is less prevalent ; however, Hikaru’s initial profession as an acrobatic pilot does from the start associate him with machines, just like Amuro’s obsession for computers. But what is more interesting in Macross is its explicit portrayal, in the form of more or less obvious easter eggs, of otaku culture. First, there is the fact that a key figure of Gainax, Hideaki Anno, worked on the TV series as an animator and left his mark on the series in many easter eggs. Moreover, we can see a short General Products ad flying by in episode 9. Finally, the characters of the three Zentradi spies sent on the Macross that become Minmay fans is without a doubt one of anime’s first self-conscious representation of otaku. Indeed, they become infatuated with the idol Minmay, just like real otakus were with real or fictional idols ; moreover, they end up selling toys, which are described as “toys plastic models”, recalling both the Gunpla boom of the 80’s and the General Products-made plastic models.

The fact that Gundam and Macross have been perceived, and are in a way, a representation of otaku is now sufficiently established. I can therefore proceed to the second and main part of my argument, which is an overview of both series’ stance towards technology and militarism, and what it reveals about the evolution of otaku mindset towards them.

Gundam and Macross : different answers, but common ambiguities

Without any doubt, Gundam and the Macross TV series can be considered as anti-war, in the sense that they both (Gundam especially) portray military conflict in all its violence and traumatic elements, and actively seek for a way to come out the vicious cycle of destruction ; it is somewhat reached in both cases, as the two series end with peace. However, the first problem such an interpretation encounters is the very nature of these works : while they apparently hold a pacifist discourse, they are still entertainment, in which the portrayal of war and violence are supposed to be fun ! This might appear as an obvious statement, but the fact that war is both attractive and repulsive is a key factor to understanding a great part of Japanese animation – Hayao Miyazaki’s complex relationship with airplane technology being another canonical example [Miyazaki, 2009 ; Lamarre, 2009].

This being said, the actual “pacifist” aim behind each of the two series is quite different, as are the conclusions reached about the achievement of peace. A brief overview will be enough to demonstrate it.

Gundam’s pacifism undoubtedly comes from its realistic depiction of war, and especially of the psychological condition of combatants and noncombatants alike. This is most notably the case of Amuro, who suffers PTSD in the beginning of the series and who has difficulty accepting his role as a military pilot. This comes to the fore most notably in episode 13, where Amuro, confronted to the dire living conditions of civilians in a war environment, is disavowed by his mother for having shot a Zeon soldier ; later (episodes 17-19), this even causes Amuro to desert. But Amuro is not the only one affected by war : episode 15’s Cucuruz Doan is an ex-Zeon soldier who fled the army after having had to kill civilians and who tries to repent by caring for the children of those he killed. As for civilians, the most tragic character is probably Amuro’s father, who became mad after having been exposed for too long into the vacuum of space. For individuals, therefore, war is but destruction and pain.

Along with war, it is militarism and the military themselves that are condemned. In the 4th episodes, which strongly announces the more vigorously anti-militaristic Space Runaway Ideon by Tomino and Macross, the White Base crew is arrested by an uncaring Federation military for violating military protocol. While the crew is later integrated in the regular army, its role as a bait and the military’s overall incompetence do not argue in its favor. But simple militarism becomes far more frightening in Zeon, as it transforms into outright fascism. Whereas the Earth’s Federation political system is not explored in detail, Zeon is clearly a military autocracy ; but most importantly, one of Zeon’s leaders, Ghiren Zabi, is explicitly compared with Hitler for his imperialist and racist ideology(4).

This racism comes from excessive hope in the Newtypes, this new step of human evolution, individuals that are endowed with psychic abilities. Zeon’s ideology is almost a religion of the Newtype, that considers them as a superior race that must dominate regular, “ancient” humanity towards prosperity. While this racist analysis of the Newtype is not shared by Tomino himself, the Newtype nevertheless is portrayed as something positive, which could very well, in fact, lead humanity towards peace. Indeed, Tomino is known for his pessimism, which includes the realistic depiction of violence, but also skepticism towards the possibility of an end to war. This is shown in Gundam both by Casval/Char’s quest for vengeance (as opposed to his sister who chose to forget and build herself a new life, even though she does end up in the military) and Ghiren’s fanaticism, which leads him to murder his own father when he starts peace talks with the Federation. However, the Newtype couple of Amuro and Lalah offers an alternative to this negative and murderous violence.

First, there is Lalah, which offers a virtuous reason for violence : that is, she fights and kills because of her love and debt towards Char. While these motives might appear egoistic, they are however portrayed as a positive motivation, an ideal worth living by. It is because of this ideal that Lalah can condemn Amuro’s meaningless fighting as “unnatural”. But what is most significant in this beautifully experimental sequence from episode 37 is what is revealed about Amuro and Lalah’s bond : even though they are enemies and Lalah ends up being killed by Amuro, they have reached mutual understanding and breached one of the major obstacles for peace. Moreover, in Lalah’s final moments, she (?) is shown running with Amuro (?) on a green field littered with flowers which evokes both the peace of afterlife and an idyllic time which would not know war. Newtypes are therefore portrayed as a metaphysical new step for humanity in what appears like a path to salvation (something which the very obvious 2001 : A Space Odyssey inspired imagery reinforces) ; and this path is not an individualistic one as, like Lalah says, “People are changing. They are becoming like us.”

If we take for granted the Newtype = otaku/postwar Japanese equation, this emphasis on the eschatological role of the Newtypes is not without consequences. Let us remember that they are not just psychics or mystics (like Lalah, whose Indian origins naturally associate her, in popular imagery, with some kind of yoga-like mysticism), but also talented individuals (like Char) and share an exceptional knack for technology (like Amuro, or the entire White Base crew, which is constituted of civilians but repeatedly defeats professional and experienced soldiers). While war and violence are the cause of trauma(5) for the young otaku male (Amuro), it is also where he is able to reveal and hone his abilities ; but also where he finds a welcoming, family-like community, exemplified by the White Base crew who welcomes Amuro with open arms in the touching final scene of the TV series. The Newtype/otaku is therefore defined by his double nature, both as a war expert and that by which war can be ended.

Macross, on the other hand, cares little for metaphysics ; its removal of any eschatological concepts and supernatural abilities is what marks its biggest difference with Gundam, but also with Ideon, with which it shares a lot of thematic and narrative elements.

But before studying how Macross ends war without eschatology, it’s important to see how it differs from Gundam in its portrayal of war. Just like in Tomino’s works, it is bloody business ; this is most visible in the instances of civilian deaths. In Gundam, already, civilians were killed ; but, except specific moments, civilian killing is somewhat of an abstract process : in the first episode, it is mentioned that entire space colonies were dropped on Earth, but the sheer magnitude and brutality of the act makes it hard to represent or picture. However, in Macross, bystanders being killed is constant, and always shown on screen. The urban warfare sequences, especially in the last episodes, are of an unprecedented intensity(6). But the main difference does not lie in the intensity of violence ; it rather is in the fact that the role of psychology and character development is completely different. As I’ve shown, in Gundam, Amuro’s psychological evolution was the result of the conflict between his hatred for war, his role as a soldier, and his trauma : his character arc consists in accepting his position as a pilot and finding a reason to fight. In Macross, these concerns are quickly brushed aside : Hikaru does suffer from the aftermath of the traumatic discovery that Zentradi look just like human beings and an intense fear of death, but he quickly recovers from it and wholeheartedly becomes a military pilot after just 4 episodes. The psychological and dramatic stakes lie rather in the love triangle between Hikaru, Minmay and Misa.

What we witness is then a step back in the depiction of war : the psychological and ethical dimension of fighting becomes less important and makes way for interpersonal drama and romance.

The same could be said about the couple war/militarism. Indeed, on the human side, war in itself is not directly condemned ; it is rather the bellicism of Earth military commanders which leads them to reject the Macross into space (another take from Ideon), refuse peace with the Zentradi and, in the end, be totally destroyed. On the other hand, the Zentradi race, engineered just for war, is another clear metaphor for blind militarism – but then, it is the one that opens itself to culture and manages to make peace with the survivors of mankind. The same could be said about Macross’s paradoxical integration of pacifism. Indeed, there is a pacifist in Macross’s cast : Linn Kaifun, who repeatedly opposes the military and denounces war. But, however valid his words may be, they are systematically disqualified by the show itself : first, Kaifun is nothing but an antagonist in the way of Minmay and Hikaru’s romance, and the viewer is therefore not inclined to look at him favorably. Moreover, Kaifun’s pacifism becomes dogmatism in the course of the series, and it is his absurd resistance to all kinds of military intervention which leads him to be taken hostage with Minmay in the end of the series : his pacifism is shown to be absurd and counter-productive.

What really becomes problematic then, is not war (or the natural tendency to violence as exemplified by the Zentradi), but culture : just like the Newtype in Gundam whose eschatological role it takes on, culture is a dual concept, the one that both ends the war and in a way prolongs or reinvents it.

Macross is famous among real robots shows for the fact that it not only depicts war, but also its aftermath : the last 10 episodes are entirely dedicated to the rebuilding of Earth and the difficulties of Zentradi assimilation. Indeed, many of the most violent of the aliens do not renounce their ways and keep wreaking havoc in otherwise peaceful towns. However, these Zentradi are not the mindless militaristic brutes of the first part of the series : they have received culture, and have changed in many significant ways. They do learn of feelings such as love, as Kamujin and Lap’Lamiz’s touching and comical death illustrates, but also of more heartless tactics such as torture and taking hostages (cf. episode 32). While it is “culture” (that is, Minmay’s songs) that allows for peace to emerge, it is not what ends the war (because some Zentradi still remain to be annihilated by military might) and also a potential cause for more insidious violence.

However, what is quite interesting, again in this final arc, is the apparent contradiction between culture and military – not in Zentradis, but in humans. More specifically, this contradiction is the driving force of most of the conflict of the love triangle, which could be read as Hikaru having to choose not so much between two women as between two lives : military (Misa) or civilian (Minmay). Indeed, it is Minmay’s growing detachment from Hikaru’s military life, which culminates with her indifference after Focker’s death, which helps to tie the bond between Hikaru and Misa ; and in the very end of the series, Minmay, now ready to relinquish her idol life, asks Hikaru to leave the military. In most of the series, therefore, Hikaru and Minmay do not communicate, because they live in different worlds.

What must we conclude of this ? I shortly touched upon it at the start of this essay, but everything Minmay related can be strongly associated with otaku activities : the lolicon movement was when idol culture started being integrated in otaku culture, and Macross represents, along with The Castle of Cagliostro and Nausicäa of the Valley of the Wind, one of the key works in the history of bishoujo characters. As I already said, this part of otaku culture is itself represented in Macross with the Zentradi fandom. An important element to note here, is that idol and pop music are all the Macross universe shows us of “culture” : no literature, no painting, no history… Therefore, according to Macross, otaku culture (karutya) represents the only form of culture (bunka). But then this culture is both antithetic with war (it is something that brings and demands peace) and a factor of perversity. However, even this perversity must be excluded from otaku custom : for otaku, war is weapons, technology and heroic battles, and not torture or terrorism(7). In other words, the Macross TV series presents us with an otaku culture that is not unified and is still hovering between a fascination for war and a fascination for bishoujo – and in the end, Hikaru chooses Misa, the military, SF way, over Minmay, the bishoujo pop idol. Otaku have lost the messianic force they had in Gundam ; but they regained it just a year later, in the alternative retelling that is the triumphant manifesto of otaku : Macross : Do You Remember Love ?

Do You Remember Love : the shift to playful militarism

It appears to me that Do You Remember Love is not just an abridged version of the Macross TV series, but an entirely different work. This means that every difference between the movie and the show is a motivated one, and will not be brushed aside by concerns about production such as taking out inessential dramatic elements. The difference between the two works lies not just in format and production values : to put it bluntly, Do You Remember Love is Macross on steroids – which means getting rid of most ambiguities. This is precisely what makes Do You Remember Love both an exhilarating movie and such an important historical document.

First, let’s quickly see what changes in the depiction of war. It is remarkable that, except for the opening scene in which Zentradi soldiers destroy Macross City and kill many of its inhabitants, civilian deaths are very seldom shown on screen ; and even though we are told that all Earth’s population has been annihilated, we do not see it being killed, as we do in the TV show ; in other words, the mass destruction remains something very abstract. Moreover, it is important to remark that, contrarily to mecha tradition (see Gundam and Ideon as well as Macross ; the same applies to later works like Gunbuster and Evangelion), at the start of the movie, Hikaru is already a pilot (just as Minmay is already a popular idol). This might not seem like much, but is in fact capital : Amuro’s central dilemma, that of a civilian being forced into the military and having to kill people against his consent, has here completely disappeared. War is taken for granted. It is even more so considering that the movie only represents the war : its difficult aftermath, one of the key elements in Macross’s “realism”, is not shown anymore.

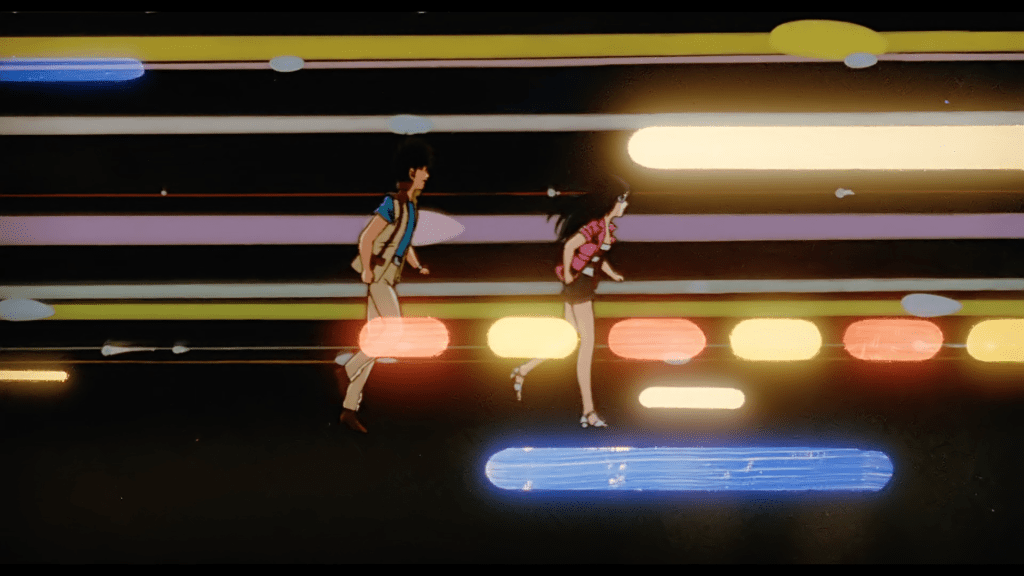

Then, there is the portrayal of civilian life, that is of “culture”. While this could be blamed on the TV show’s poor production quality, Macross City was originally a nondescript and not particularly attractive town. However, in Do You Remember Love, it becomes a cyberpunk template, without the rain and sinister atmosphere ; in other words, it is a utopia of Japanese 80’s capitalism. The scene of Minmay and Hikaru’s date shows us a bustling city, with pop music blasting, neon flares everywhere, French fashion shops, fast-foods, and even love hotels ! The cosmopolitanism, and consumerism, characteristic of later Bubble-era Japan are here presented as positive aspects, and Macross City is an attractive, prosperous (not that) futuristic town, and not the frail refugee settlement that it is in the show. “Culture” is then not only idol music and its otaku fandom : it is late capitalism at large. Do You Remember Love’s position is both more general (it does not only apply to otaku) and more particular (culture is equated with consumerism).

But the difference becomes even more striking if we look at two parallel sequences : that of the final battle against the Zentradi, in episode 27 of the TV show, which is the final scene of the movie. Both battles are accompanied by Minmay’s songs ; but there is a clear thematic and tonal difference between these. In the TV show, Minmay starts with her three standards (My Boyfriend Is A Pilot, Shao Pai Long and Shanghai Dandy), all three cheerful tunes. But then she sings a fourth and final song, Love Flows By, which is the one that is played during the final demise of the Zentradi, and therefore leaves the most impact. The lyrics are without a doubt anti-war : “I know you’re going off to war / All the men, as if possessed / With mouths pulled tight, with eyes burning / I know I’ll be left behind / All for war / All for pride […] / I’m certain I’ll always hate war […] / Stop the war, all for the cause of life”. The movie’s titular song, Do You Remember Love ? is quite a different story. Misa describes it as “just an ordinary love song”, which it is, and the fact that it has not been written by Minmay but is a relic from the Protoculture detaches it from any context, most notably that of the battle going on or of the love triangle. The effect produced is therefore very different : on the one hand, we have a bloody battle, which is supposed to end war, accompanied by a pacifist song ; on the other, it is the same battle, but what is at stake is only the survival of humanity, which is encouraged by pop music.

The cinematography is here very telling : Do You Remember Love’s battle is directed just like a music video, in which Minmay’s singing and the fighting are complementary. This is a key element in the movie’s new take on war and culture. Indeed, in this scene, Minmay does not sing from afar ; on the contrary, it’s like she’s at the heart of the battle. Moreover, in the last shots, where the leader of the Zentradi is killed, Minmay is shown just behind Hikaru delivering the finishing blow : it’s just like Minmay is the one sending the Valkyrie or, in other words, like it’s Minmay herself who’s killing the bad guy and triumphing in this battle. This new role of culture is also evident in the way the Zentradi refer to it : in the TV show, it is something incomprehensible and mystical, described as a “sickness” – something maybe directed by the humans, but which has an independent existence. However, in the movie, it is described as a brute force (chikara) : that is, as a weapon manipulated by humanity.

I believe that these points show well enough how Do You Remember Love thematically differs from the original Macross : all ambiguities have been ruled out, and a synthesis between war and culture is reached. Culture, that is capitalism modes of consumption developed in Japan, has become both an ideal and a tool. Otaku, the audience of the movie, are necessarily at the forefront of this new kind of capitalism ; their appreciation for both war and idols make them the perfect vanguard of consumerist culture.

Conclusion

This essay relied on two premises : first, that the historical association between otaku and militarism is a well-founded one ; second, that otaku were both the audience and the object of the first real robot shows. Once these assumptions are taken for granted, I believe we can see a clear evolution in the otaku mindset and its position towards postwar, pacifist Japan. From a mainly critical position (Gundam) that positioned otaku and their special understanding for technology as a key requirement for peace, we end up in an enthusiastic celebration of late capitalism and otaku culture as its forerunner (Do You Remember Love ?).

I have here insisted on continuities and evolutions between the three works, as my approach was mainly a historical and genealogical one. However, discontinuities exist, not in the direct intertextuality between the series, but in the different socio-economic contexts in which they take place. Gundam is still very much a product of postwar, “economic miracle” and reconstruction Japan ; the influence of WWII, the 60’s leftist students movements, and the Vietnam War, can still be seen. However, Macross is a pure product both of otaku culture (from Studio Nue to Hideaki Anno) and the 80’s economic bubble, an unprecedented era of prosperity for Japan. These external factors may very well be the cause of the huge tonal difference between Gundam and Do You Remember Love ? The same could be said about later works, which would have to be studied as well for this historical survey to be complete : I am mostly thinking about Hideaki Anno’s works. First Gunbuster, which is but a prolongation of Do You Remember Love’s celebration of playful otaku militarism, even though war is not even a problematic element anymore. And second is obviously Evangelion, which is at the same time a celebration of otaku culture, an uncompromising condemnation of the playful militarism of the 80’s, and a reflection of 90’s Japan faced with economic depression, devastating earthquakes and otaku-inspired murders and terrorist attacks. All of these elements are what truly make of Evangelion, more than Gundam, the harbinger of a new century – that is, a profound mutation of otaku culture.

Notes

(1) For reference, I here note that at the time, in these circles, “lolicon” simply meant appreciation/love/sexual attraction to fictional characters, most notably shoujo manga’s and was somewhat of an equivalent to what we now call “moe” ; it did not, then, include a reference to children or childlike characters [cf. Galbraith, 2015]

(2) Indeed, as the quote above illustrates, “otaku” was used as a pejorative term by Nakamori ; even though the issue is complex (see Galbraith, 2015), Nakamori, despite writing in a lolicon magazine, sought to distance himself from this part of the community – therefore focusing on difference rather than common tastes

(3) This while acknowledging their imperfections, fears, etc. that contribute a lot to the realism of both series ; however, just like Shinji in Evangelion which in the end does come out of his depressive state and this way acts as a model despite his partly despicable personality, I believe that Amuro and Hikaru are positive figures

(4) Following Mizuno’s [2007] interpretation of Space Battleship Yamato, we could read this equation of antagonist Zeon to Nazi Germany as another of attributing imperialism and racism in WWII to Germany rather than Japan

(5) Which we could interpret with Takashi Murakami as the original castration which led to otaku’s fascination for war and military technology

(6) Except if we consider Ideon, which was probably Macross’ biggest influence, both in its ruthless depiction of violence and hatred for militarism

(7) Which it will, in a way, become in the 1990’s with the Aum Shinrikyou sarin gas attack

Bibliography

Aida, M. (trans. Galbraith, P. 2015) “The Construction of Discourses on Otaku : The History of Subcultures from 1983 to 2005”. In Galbraith, P., Huat Kam T. and Kamm, B.-O (ed.) Debating Otaku in Contemporary Japan. Historical Perspectives and New Horizons. Bloomsbury Academic.

Azuma, H. (translation J. Abel and S. Kono, 2009) Otaku. Japan’s Database Animals. University of Minnesota Press.

Hiromi, M. (2007) “When Pacifist Japan Fights : Historicizing Desires in Anime”. Mechademia. Vol. 2, 2007, “Networks of Desire”. University of Minnesota Press.

Lamarre, T. (2009) The Anime Machine. A Media Theory of Animation. University of Minnesota Press.

Miyazaki, H. (translation B. Carry and F. Schodt, 2009) Starting Point, 1976-1996. Viz Media.

Murakami, T. (ed., 2005) Little Boy. The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture. Japan Society, Yale University Press.

Otsuka, E. (trans. Lamarre, T., 2008) “Disarming Atom : Osamu Tezuka’s Manga at War and Peace”. Mechademia. Vol. 3, 2008, “Limits of the Human”. University of Minnesota Press.

Takeda, Y. (2005) The Notenki Memoirs : Studio Gainax and the Men who Created Evangelion. ADV Manga.

Okada, T. (trans. Galbraith, P. 2015) “Introduction to Otakuology”. In Galbraith, P., Huat Kam T. and Kamm, B.-O (ed.) Debating Otaku in Contemporary Japan. Historical Perspectives and New Horizons. Bloomsbury Academic.

Otsuka, E. (trans. Galbraith, P. 2015) “Otaku Culture as “Conversion Literature””. In Galbraith, P., Huat Kam T. and Kamm, B.-O (ed.) Debating Otaku in Contemporary Japan. Historical Perspectives and New Horizons. Bloomsbury Academic.

Yamanaka, T. (trans. Galbraith, P. 2015) “Birth of “Otaku” : Centring on Discourse Dynamics in Manga Burikko. In Galbraith, P., Huat Kam T. and Kamm, B.-O (ed.) Debating Otaku in Contemporary Japan. Historical Perspectives and New Horizons. Bloomsbury Academic.

One thought on “Militarism and otaku identity : from Gundam to Macross”